The amazing thing about searching with Google is that not only can you find a needle in the internet haystack—sometimes you find needles you weren’t even looking for, like this story of Richard T. Underhill’s involvement in the West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway Company, the company that began the New York City transportation system.

First some background, courtesy of the Mid-Continent Railway Museum in New Freedom, Wisconsin:

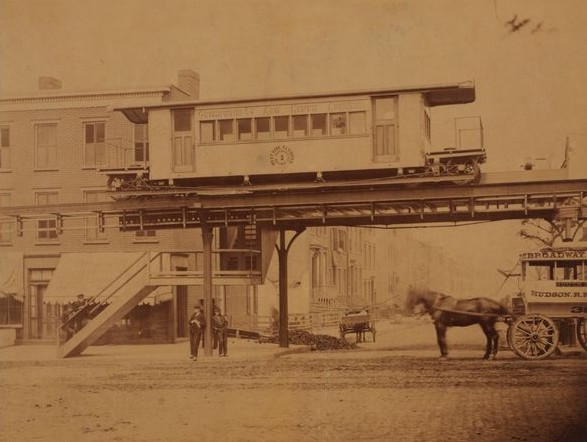

“In 1867, Charles T. Harvey (1829-1912), a self-trained civil engineer . . . built an experimental single-track, cable-powered elevated railway from Battery Place, at the south end of Manhattan Island, northward up Greenwich Street to Cortlandt Street. His company had been chartered the year before under the name of the West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway Company, with subscribed capital of $100,000, to build a 25-mile elevated railroad from the southern extremity of the city northward through the city and thence to the village of Yonkers.

The half-mile line was dubbed the “one-legged railroad,” because the single track ran above the street on a single row of columns. The cable was a loop, driven by a stationary engine, that ran between the rails for propulsion of the cars, then returned under the street. The concept was similar in many respects to that used by the San Francisco cable cars five years later—the primary difference being that Harvey’s patent called for the car to be secured to the cable by a sort of claw that would grab onto metal collars woven into the cable rather than a Hallidie-type “grip.”

shown in 1869 at the 29th Street Station.

The line opened for business July 1, 1868, and [after] the State Commissioners who authorized the “experiment” . . . declared it a success, the Governor authorized its completion to Spuyten Duyvil . . .

But the line had ongoing problems. The mechanics of grasping the cable proved less-than-perfect. Maintaining the mile-long cable was a problem. Having it “return” under the street was a problem that was soon fixed by having it return at track level, but it still had to be directed off the track and into the building where the stationary engine sat. Legal problems were constant, largely at the instigation of those who wanted the franchise for themselves.”

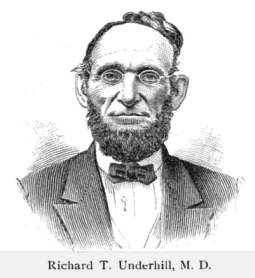

In his 1890 book The Most Notable Robbery of Modern Times—about the legal and financial chicanery in the early New York City transit system—Stephens O. Jennings wrote about Richard Underhill’s role as an investor in the West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway Company. Jennings knew Underhill personally and he not only adds to our knowledge about the “Grape King” of Croton Point, he prints a portrait of Underhill as well.

According to Jennings, Underhill “appreciated the desirability of more rapid transit between his country residence and city office, and at an early date investigated and advocated Mr. Harvey’s plans as having the germ of the greatly needed boon.”

The Most Notable Robbery of Modern Times

by Stephens O. Jennings, 1890.

“Dr. Underhill became a subscriber; he . . . gave personal attention to the progress made, and counseled with the projector in his arduous labors. In like manner Dr. Underhill’s memory should be coupled with the elevated system, and one incident will suffice to show the propriety of so doing.

As the time drew near in 1870 to open the railway to public use, he counseled great care in proving its safety.

A car loaded with a heavy test weight of pig-iron was drawn over the line by horses with satisfactory results. But this did not show the effects of speed, and Doctor Underhill favored a test as to that element of danger. Accordingly one afternoon, the test car was coupled to a passenger car, to be run over the route by the cable machinery. The Doctor, Mr. Harvey, and [this] writer entered the car, which was soon running at high speed. At the longest bridge and sharpest curve in combination on the route, the centrifugal force of the load shifted the supporting beams and bent a column arm, causing a section of the track to slide into the street below, and the car with its three inmates also went down. Providentially, no one was injured. When the track was repaired and new safe guards added, the same test was again applied, but at day-break, to avoid the previous danger to those on the street surface. Dr. Underhill had learned of the time, and, to the surprise of us all, appeared at the station at the dawn of the day and insisted upon going with the party as before. The trip upon this occasion was made without accident, and at its close he grasped Mr. Harvey by the hand and said, ‘Now we can conscientiously recommend this road as safe.’ The doctor was correct, as statistics show that that railway and its extensions transport passengers with less casualties per capita than any other in the world.

. . . New York City is indebted to [Underhill] to a marked degree for its present transit comforts.”

Now this was REALLY SUPER.

You are sadly incorrect about the IXL on the Underhill bricks meaning “I excel.” They were in fact the stamp from an IXL brick making manufactured at Croton by W. E. Talcott who was an Underhill in-law. His IXL brick manufacturing machine was considered the best on the market around 1892. In 1896, W.A. Underhill bricks ordered a new brick machine from Talcott for the north yard.

Great to hear from you. I know about Talcott and have a wonderful ad for his IXL machine that I’m planning to post at some point. Since Talcott was related by marriage, how do you know that he didn’t name his machine after the Underhill motto?