Now that “Autumn is touching with wary finger the wealth of forest and orchard, and carefully-tended garden spots,” let’s open our copy of the New York Times—from October 23, 1862—and read the letter, The Season of the Vintage, the Croton Point Vineyards, to learn about the “commodious and cool” wine cellars, the clever “Yankee” solution to an invasion of “ground moles” and the plum-tree lake, where the trees are “planted as to hang directly out over the water” and the ripe fruit is “gathered in boats that moor immediately under the branches.”

“. . . granaries are bursting with the harvesting of the Summer’s generous growth, and the Autumn is touching with wary finger the wealth of forest and orchard, and carefully-tended garden spots, the vineyard, with its drooping clusters, claims our admiration. The wine-growers carry cheerful faces now, for along with the luxuriant abundance that has marked the growth of other fruits, the grape is worthily conspicuous. The hillsides of La Belle Riviere,1 and the southern slopes just off from the mad Missouri, sends us their brands of “Catawba” still, or sparkling, their sharp “red wine” and mellow native brandy; but in all these lurks a touch of grossness when compared with the home growth of our Croton and other vineyards. The “Union” wine, which, aside from its patriotic signification, is made up of a union of the two popular growths of Isabella and Catawba, is the unadulterated juice of the berry.

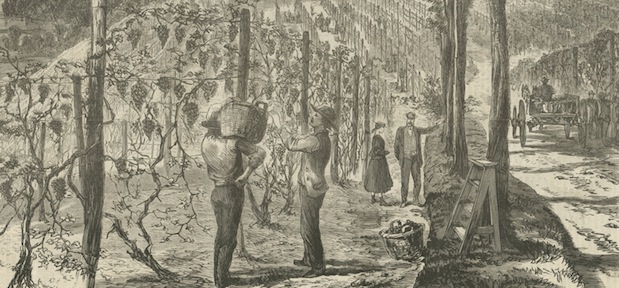

Having visited the Croton Point vineyards while the luxuriant harvest was at its height, some things were observed which you may find noticeable. Almost within sight of Manhattan Island, a narrow point projects suddenly from the main land into the Hudson, whose waters wash its west bank, the Croton River forming its eastern boundary. This grassy, well-wooded point divides the river into two bays—the one lying above called Haverstraw, and the one below, Tappan Zee—names whose origin needs no explanation to New-Yorkers. Upon the opposite shore of the Hudson there are wild mountains, frowning darkly, and bristling with rocks, upon this saucy little point making out so boldly into the middle of the river, and threatening to come clear across and bloom and blossom about their very base; but the rural hamlets peeping out from the cultivated valleys preserve the balance of cheerfulness, and the mountains frown on in silence, and the saucy little point glories in the admiration of passing voyagers, and entertains by shoals her friends, the shad, the perch, and striped bass, that play about her pebbly borders to the music of dashing spray and whispering pines. She flings a breath of redolence to the peaceful hamlets, and sighs through all vineyards for the desolate, grim old mountain. Between forty-five and fifty acres upon the Point are now covered with richly bearing vines. After many unsuccessful efforts to perfect foreign varieties, Dr. Underhill has settled upon the two familiar staples, the Isabella and the Catawba. These, he is persuaded, meet—all things considered—the demand for table, for general market supply, and for wine. The successful cultivation of these sorts has been carried on since 1834, and his plan is quite different in the rearing and training of the grape from that practiced in Europe, and upon our western border. He does not wind his vines around upright stakes, as is common, but he trains them along wires which are secured to posts some seven or eight feet high. The strain upon these posts is so great that they are driven four feet into the ground.

The plants are never allowed to be forced, either in the nursery, or afterward in the vineyard. This would, indeed, produce large sap vessels, but would render the quality inferior, and subject the plants to “Winter kill.” The larger the sap vessels the greater the quantity of water, and the less the saccharine element, and, necessarily, the poorer the wine; for what dilutes the substance of the berry dilutes the wine. In order to concentrate the desirable qualities, the vines are subjected to a Winter as well as a Summer pruning. During the early Summer, after the berries are fully formed, a thorough pruning takes place. Every extra shoot, besides many hundreds of young bunches of fruit, are lopped off, leaving the whole strength of the vine to transfuse the remaining clusters. At the present season of the year, or earlier, when the crop is in full perfection, men accustomed to the cultivation of the grape in Europe are employed to garner it. The bunches are carefully supported while the pruning-knife does its work, and the rich masses are carried by huge basket loads into the “fruit house,” where woman's more delicate touch is brought to bear in culling every defective berry from each cluster, and placing them one after another in layers between light wood slats, with which the receiving-box is supplied. This box is then stored away for preservation till the market demand shall reach it. Baskets for ready use are also at hand, provided with wooden lids, which serve to transport the fruit to the city to supply the immediate demand of fruiterers, grocers, &c., &c.

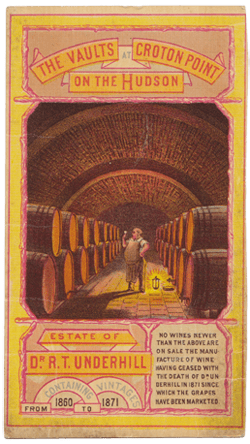

The transportation is always by means of steamboat, the jarring of railroad being considered damaging to the mellow fruit. Beside this immense supply to the fruit market of New-York City and vicinity, there are hundreds and hundreds of bushels made into wine, and stored away in casks containing 800 gallons each. These occupy a row of hillside cellars, or vaults, arched, commodious and cool, with every conceivable adaptation to their use. In one of these cellars the wine press is situated. It is a disappointingly small affair, but one has to remember the slowness and gentleness with which it acts upon its quantum of grapes, and with what perfection it expresses their delicate virtues. The work is not hurried, and the pressure upon the mash is cautiously regulated. Perhaps this accounts for there being no skin flavor nor indefinably gross taste about the several varieties of Croton Point wine. The great casks are fed by hose running from the vat, and after age has laid his seal of excellence upon them the contents are drawn off in bottles and garnered in the great cellars below the general depot in Astor-place. The great casks and lesser barrels employed are all the work of home laborers; all the mechanical appliances of the place are from the workshops upon the grounds. Coopers, blacksmiths, carpenters, &c., are constantly employed.

Ground Mole Dogs

A trial to the spirit of wine growers is the ground mole. For the last twenty years it has been an increasing and much neglected evil all over the country. In Germany and other old countries of Europe, men are regularly elected whose business it is to exterminate this nuisance. They have numerous traps wherewith to make their raids, effectual; but Dr. Underhill having no such resource, and being, withal, a bit of a Yankee, has trained a band of little dogs, who let daylight in upon these stealthy borrowers in an entirely irresistible manner.

The Plum-Tree Lake

These grounds of Croton Point were, naturally, largely composed of mineral substances; consisting principally of fine granite, silex, oyster shells, &c., &c., combined with which was very little of vegetable matter. To supply this ingredient large alluvial deposits have been removed from near the mouth of the Croton River, leaving an excavation which has been filled to the forming of a beautiful lake, into which, by a sluice way, the choicest fish, as yellow and Croton-striped bass, white perch and sunfish make their way and are easily caught.

The main feature of this lake is, however, its complete border of plum trees, so planted as to hang directly out over the water. This plan is the result of experiment and conclusion arrived at by the Doctor, that the insect known as the “curculio,”2 whose ravages have defeated the utmost care of plum-growers, will not sting the fruit that hangs over water. The plums, when fully ripe, are gathered in boats that moor immediately under the branches. A very large crop has been gathered here at times when an utter failure has marked the country elsewhere. A nectarine pond is commenced upon the same principle.

Beside the almost illimitable variety of less important fruits, the monotony of the vineyards is relieved by orchards of Newtown pippins, the rich apple quince, pears, &c., &c. As for mammoth pumpkins—seedlings of other climes, both tropic and temperate—it is not consistent here to speak; but a visit to a Hudson River vineyard, with all its glorious resources of hill-side, valley, river, and mountain view, is something strangers from afar take delight in accomplishing, and our own citizens must be proud to enjoy.”3

- La Belle Riviere (the Beautiful River) was a 19th century name for the Ohio River, which had become a grape-growing area when this article was written. ↩

- Plum curculio is a major insect pest of apple, plum, apricot and cherry, and a minor pest of pear and peach. See the University of Maine Cooperative Extension website. ↩

- This letter was anonymously attributed to “R * * * * *” ↩

I loved the idea behind “Plum Lake”