LIQUOR LADEN PLANE FROM CANADA FALLS AS IT NEARS CITY

Drops 250 Quarts of Scotch Near Croton, Where Water for Highballs Comes From

FLIER ESCAPES IN AN AUTO

Car Apparently in Waiting Whisks Limping Aviator From Scene

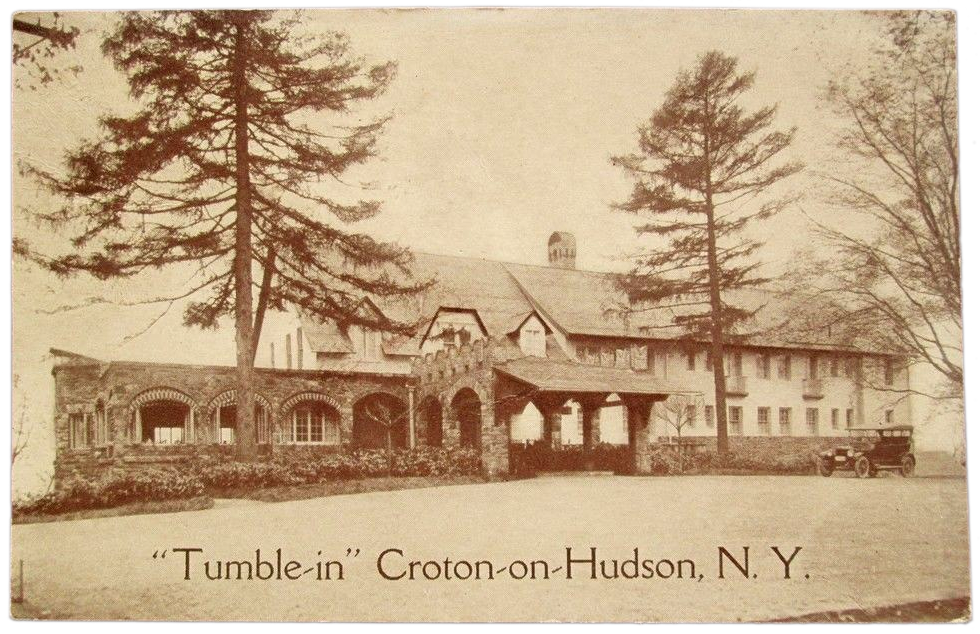

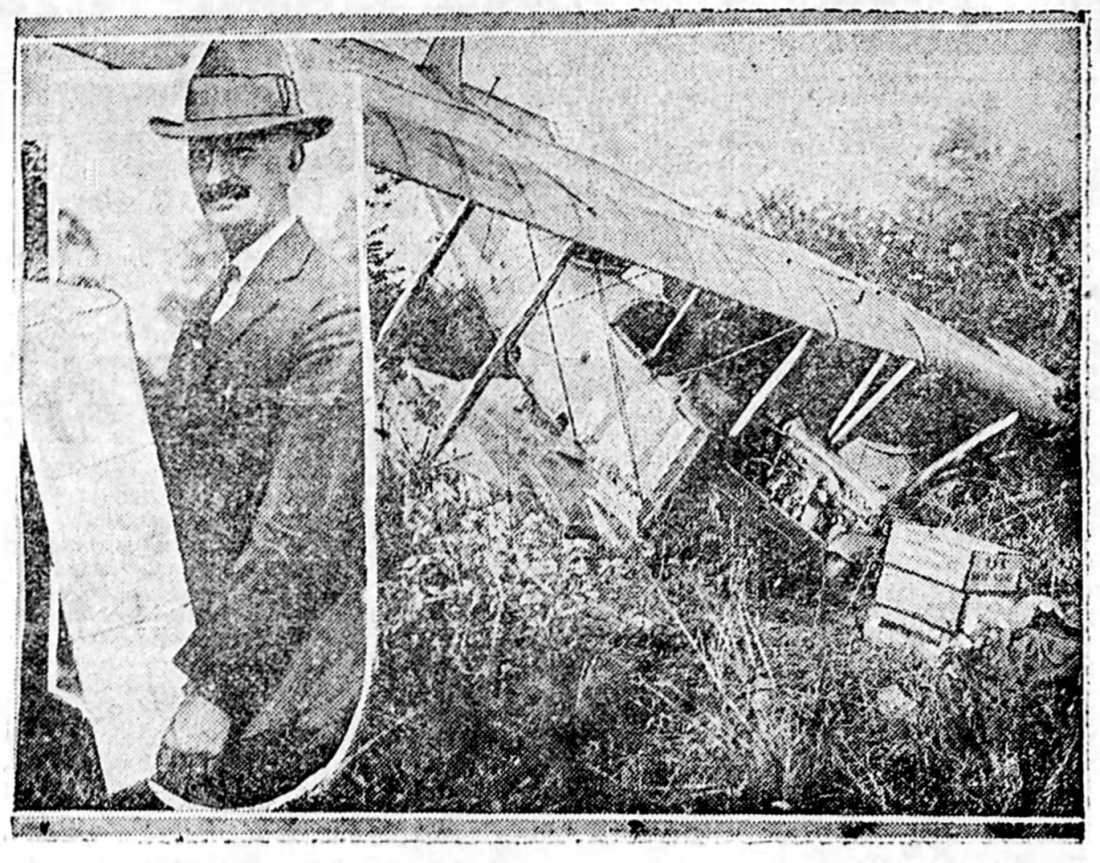

“Dusk was deepening into darkness” on the night of May 15, 1922, as a Curtis biplane circled slowly over a farm “about a mile and a quarter above Croton . . . a quarter of a mile from Tumble Inn, one of the much patronized roadhouses of the county.”1 The farm’s owner, former Westchester County deputy sheriff George McCall, watched as the pilot “suddenly pointed the craft’s nose earthward and slipped toward the farmhouse.”

As the New York Times reported the next day, “something about the landscape did not please [the pilot]. No one could figure out afterward whether it was the lay of the land itself, or whether his clandestine errand made the proximity of the house a paramount objection. At any rate, the pilot suddenly quickened his engine and climbed heavenward again. He flattened his course at about 1,000 feet and circled over the farm. Along the road a number of persons . . . were craning and watching his maneuvers.” Suddenly the pilot “evidently made a sharp decision to come down. It was thought afterward that he might have spied an automobile that was drawn at one side of the road not far from the farm.”

“By then it was black night, and the task that faced the pilot . . . was severe. He made no attempts to get back to the level fields near the house. Instead, he came thumping down on a side hill that he may not have even discerned in the darkness. The nose of the plane dug into the earth, the wings crumpled and the ruptured tank sent a geyser of gasoline spraying over the whole craft,” which miraculously did not catch fire.

Gasoline wasn’t the only thing that sprayed out of the plane. When McCall raced to the wreck he “caught the odor of whiskey above the smell of hot gasoline and oil.”2

McCall feared the pilot was dead, but “instead of the body he found a wrathful and limping man, making good time toward an automobile that waited . . . door yawning hospitably.”

“The pilot paused only long enough to say that he was not badly hurt and to mumble something about going to the village to get some one to care for the plane. Then he entered the car and was whizzed away.”

McCall called the police and “Captain Warner, Lieutenant Roberts and three troopers piled into an automobile and burned up the miles from White Plains.” When they got to Croton “they found a little group of country folk grouped about the battered remains of a once gallant craft, some of them looking quite cheerful over that which the air had provided, others shaking their heads in grief over . . . what had once been perfectly able-bodied whisky bottles.”3

Speaking “out of professional knowledge, gained in enforcing the prohibition laws in the wilds of Westchester,” Captain Warner said the whiskey was of “excellent quality.”

The plane had two cockpits. The forward one had been used by the pilot and the other was crammed with burlap sacks of liquor bottles—some broken, many intact. In all there had been some 250 quarts of Scotch and Irish whiskey. All the bottles bore the tax stamp of the Quebec liquor commission.

According to the Times, the bootleg market price for Scotch and Irish whiskey in New York was then about $15 a bottle, so the cargo would have fetched about $3,750. In Canada the cost per bottle was $3, so even if the rum runners paid the pilot $1,000 for his work they would have made a profit of $2,000 for a single trip.

Aerial Rum Runners

A search of the airplane the next day revealed a “worn chart, which obviously has traveled many hundreds of miles pressed between the knees of a pilot” giving officials “tangible evidence of a prosperous rum running business by air. They also saw why Westchester county, with its numerous roadhouses and thirsty, well to do people, has so many aerial visitors. Quite a few airplanes have been flying over Westchester lately, some running low and out of gliding distance of the river. It was conjectured that many of these may have been laden with bottles like the mystery plane which fell at Croton.”4

The map was found by George McCall, who connected the arrival of the plane with the appearance two weeks earlier of a mysterious car which halted on the Albany Post Road, near where the pilot had tried to land. The car stayed until 4 o’clock in the morning and a few hours later McCall found his watchdog dead.

A careful examination of the map revealed that the pilot had flown from Montreal to Glens Falls, NY, where he stopped to refuel. From Glens Falls a black line followed the Hudson River to Croton, where the line forked. One branch ran to Briarcliff, across Westchester County to Stamford, CT, then south to the Long Island Sound. The other branch ran south from Croton to Manhattan.

The use of airplanes to transport illegal liquor to New York was shocking in 1922 and the Croton “rum plane” crash was covered widely in the press. An enterprising reporter in Buffalo—a center for smuggling from Canada—decided to ask the city’s “favorite law violators” what they thought. “Very Few Aerial Rum Runners Here,” read the headline, “Only Prices Aviate, Say Bootleggers, Who Surely Know.”

“‘In the first place,’ declared one bootlegger, ‘we don’t need airplanes in Buffalo. We need boats. In the second place the cost of operating and maintaining an airplane would make the price of whiskey prohibitive. A pilot’s salary is considerably more than a chauffeur’s. Airplanes are not so common that they can come and go, landing where they find it convenient. Fields must be provided, and there is slight chance that they would utilize a regular landing to bring in whiskey. I believe that the plane . . . was probably the private property of some wealthy man who wanted the booze regardless of cost.’”5

Supporting the bootlegger’s theory was the fact that “the whiskies were of various brands,” which led authorities “to think some chap with sporting blood decided to take a plane to Canada and fill an order for half a dozen friends and bring back just the particular Scotch or Irish each one liked. Some of the sheriffs who have had to do with seizures by truck stated that in these seizures the goods in nearly every case were of one brand only.”6

Powder Puff Pilot

In addition to the route map the police found “a vanity box, powder puff and several articles of feminine attire,” leading to speculation that the pilot had a woman’s aid or—despite George McCall’s eyewitness account—that the pilot was a woman.7

The “powder puff pilot” theory was given credence by the extraordinary confession of one of seven rum runners captured on a converted submarine chaser off the New Jersey coast, two days after the rum plane crashed. The ship was seized with a cargo of liquor worth $200,000 from the Bahamas by an American “rum cruiser.”

The New York Tribune reported that the confession “goes far to explain the female toggery in the captured airplane. According to it, girls and women are regularly employed in an aerial rum running traffic between Montreal and New York. . . . Detailed information, including the names of a score or more women rum runners, with registry numbers of planes as well as of auto trucks and marine craft engaged in the trade are said to be included in a document of some 5,000 words in length.”8

A Croton Connection?

Was it a mere coincidence that the rum plane crashed so close to the Tumble Inn, one of Croton’s notorious speakeasies? Since the area is so hilly it’s hard to imagine where the plane would have landed, but why was a car waiting to whisk the pilot away?

Only a few weeks before the crash the Tumble Inn had been raided, after a waiter handed a neatly printed wine list to a diner, Ralph A. Day, who happened to be the Federal Prohibition Director for the State of New York.

When Day returned to his office he sent several agents to have a nice dinner at taxpayer expense and “dry up” the Tumble Inn. The agents were served several different kinds of wine with their meal and when they were finished they arrested the head waiter, John J. Jenkins, and waiter Joe Acerboni. The New York Evening World reported that “although the dining room was crowded with guests when the arrests were made . . . few knew what was taking place.”9

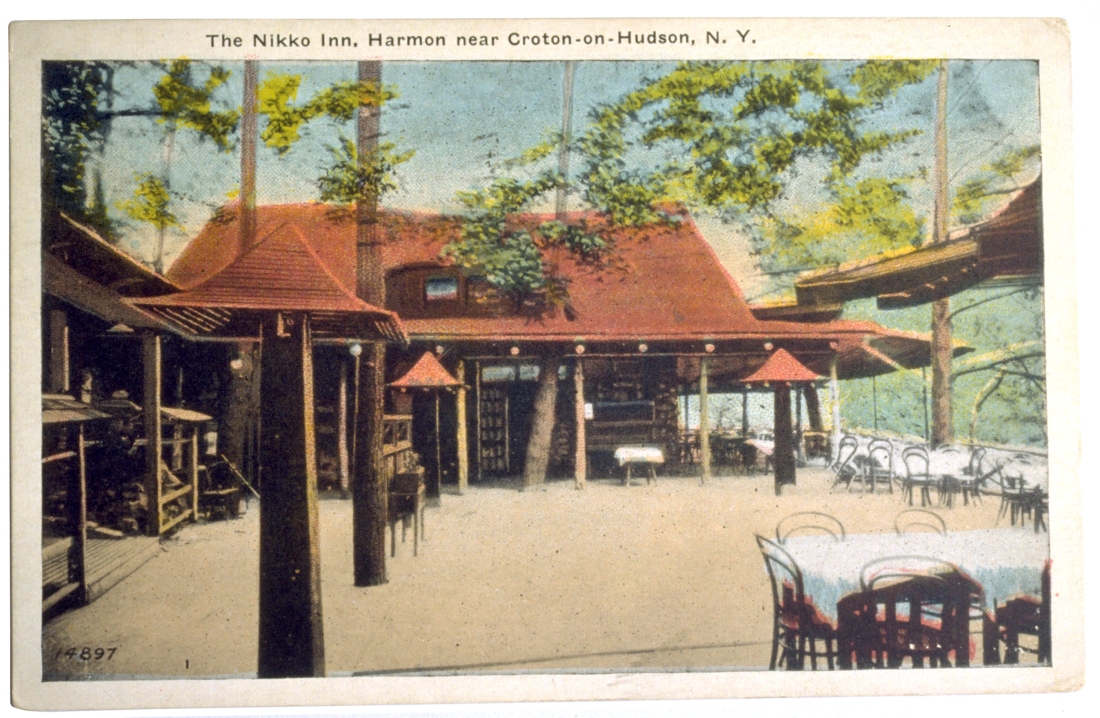

A month after the crash the Nikko Inn was busted by agents who represented themselves as actors. The New York Times reported that “Charles Hase, the owner of the place, asked them to ‘do a turn’ for him. McKay fiddled, Reager sang and Gallante danced. The innkeeper was satisfied with their work and was about to hire them, when the agents, after having been served with drinks, as they alleged, at $1.50 a drink, arrested Hase and a waiter, Hero Gotow, on a charge of violating the Volstead act. They gave $1,000 bail each for appearance . . . before a United States Commissioner.”10

Across the street from the Nikko was the Mikado Inn, built around 1920 by “Admiral” George T. Moto. A year before the crash Moto was acquitted “after five minutes deliberation” in what newspaper accounts at the time called the first case to be tried in Westchester County for an alleged violation of the New York State liquor law.11

One Last Mystery

In addition to the pilot’s identity and gender, the suspicious presence of a waiting car, and the possible Croton connection, there’s one last mystery.

Two days after the crash an article in the New York Evening World reported details not found in other accounts. After describing the discovery of the map and “several articles of feminine attire” the article states that “information obtained today indicates an attempt was made to recover this map from the wreck. Among those who visited the scene yesterday was a young man in a naval aviation uniform. He said he heard the machine had been abandoned and he thought there might be parts he could salvage. According to Dr. Miller of Croton12 a man in the uniform of a naval aviator reached the plane soon after it crashed and called to the pilot, naming him ‘Bill,’ to ask what had happened. The pilot replied that his engine had ‘gone back’ on him. Then the pilot and the naval aviator got into an automobile and drove away.”13

Who was the man in the naval aviator’s uniform and why did George McCall not mention him in his account of the crash?

Learn more about Croton in the Prohibition era:

- Rum-running Submarines off Croton Point?

- The Motorist’s Playground

- Oscar Levant Plays the Mikado

- A Delightful Place to Dine

- Roy Kojima, Busted and Boastful

- Our Multi-Talented Federal Prohibition Agents

- If You Follow the Road to Harmon, You Surely Can’t go Wrong

- Tumble Inn

- Mikado Inn “Real Photo” Postcard, circa 1920

- This is Mikado Inn

- What’s Cookin’ at the Mikado?

- Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from the New York Times article “Liquor Laden Plane from Canada Falls as it Nears City,” May 16, 1922. ↩︎

- “Busy Liquor Route is Shown on Air Route Map,” The Journal & Republican, Lowville, New York, June 1, 1922. ↩︎

- Newspaper accounts differ on how many bottles were in the airplane and how many were broken in the crash. The headline of the New York Times article correctly said the plane had 250 quarts but the text had a typo and reported the quantity as 150 quarts. Many newspapers picked up the lower number. The Times reported that “about 100 bottles had been smashed.” ↩︎

- The Journal & Republican, Lowville, New York, June 1, 1922. ↩︎

- “Only Prices Aviate, Say Bootleggers, Who Surely Know,” Buffalo Courier, May 21, 1922. ↩︎

- “Hooch Airplane Captured by State Troopers,” New York Evening World, May 16, 1922. ↩︎

- The Evening World, New York, May 17, 1922. ↩︎

- “Powder Puff Betrays Woman as Pilot of Wrecked Rum Plane,” New York Tribune, May 17, 1922. ↩︎

- “Inn’s Wine List Gets Inn In Bad,” The New York Evening World, April 4, 1922. ↩︎

- The New York Times, June 17, 1922. ↩︎

- “Westchester Innkeeper Acquitted in Liquor Case,” New York Evening Telegram, July 12, 1921. ↩︎

- Additional research is needed, but articles in the Peekskill Highland Democrat in 1917, 1926 and 1927 refer to “Dr. Miller of Croton.” ↩︎

- “Sky Runner Had Woman’s Aid Is Now Believed,” New York Evening World, May 17, 1922. ↩︎